Thelma Golden, Director of Exhibitions and Chief Curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, famously added a new word to the art-historical lexicon by declaring, in her essay for “Freestyle,” the landmark 2001 exhibition of emerging Black artists, that “post-black” was the new black. A number of artists from “Freestyle” have gone on to enjoy solid artistic careers, including Rico Gatson and Sanford Biggers, both of whom were recently the subject of survey shows in New York.

As a provocative descriptor of identity that does not identify and politics that are apolitical, “post-black” had been used in scholarly discourse for at least 10 years prior as a way to define a black cultural aesthetic in a multicultural, post civil rights world. Although Golden is credited with giving the concept traction and viability in the art world, the term post-black has not always been embraced. Although one might argue that the exhibition shifted the discourse about blackness away from representation and towards abstraction, the way that Gatson and Biggers have portrayed issues of Blackness in contemporary society through their art is anything but coy, ambiguous, or post-anything.

Exit Art’s “Three Trips Around the Block” is a 15-year survey of sculpture, painting, video, and installation by Brooklyn-based Rico Gatson. Much of his work deals with the various modalities of being a Black American through images of historical and pop cultural icons, significant historical moments, and events. Gatson’s aesthetic draws heavily on Minimalism, and the patterns in his paintings, and the sleek, clean lines of his sculptures affirm this, although he does not simply pluck characteristics from Minimalism blindly without offering any sort of critique. Many of the paintings, like Untitled (L.A. Riots) (2011), often employ glitter and sparkles as an additional layer on top of the pigment. Black silhouetted figures are glitter-laden in the foreground, their hands and fists raised in front of a fire-lit sky of mauves, purples, blood oranges, reds, and blue-grey smoke. The wall sculpture, Mystery Object #3 (2011), nods to Donald Judd with its black acrylic painted wood (enhanced with glitter) that forms neat rows over orange Plexiglas. Sculptures like Whipping Post and the paintings Approximation of the Ku Klux Klan Symbol and Iraqi Landscape (all from 2006) use a color scheme commonly found in African cloth: blues, reds, oranges, and yellows – underscoring the artist’s concern with histories, legacies, and lineages.

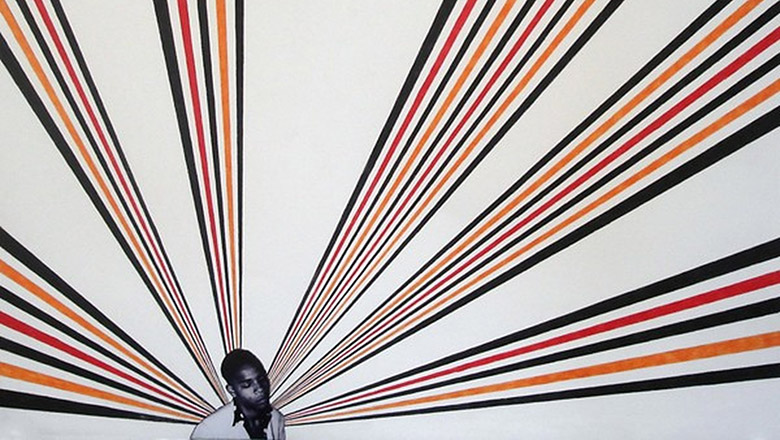

A series of works on paper feature popular icons like Lena Horne, Stokley Carmichael and Langston Hughes. For these images, Gatson added black-and-white beams radiating off of each figure, sometimes adding a splash of color. Double Hughes (2011) places the same image of a young Langston Hughes in the opposite bottom corners of the paper; the rays between the two images are imply the greatness of the pyramids. In Lena #3 (2011), the singer is set squarely in the center of the rays as if she were the sun itself.

The most arresting work in the exhibition is also its earliest. Two Heads in a Box (1994) hangs from the ceiling in the back gallery as an unassuming pine box with music playing inside. A hole in the bottom of the box is large enough for a viewer’s head, and once one looks inside, we can see a video loop of the artist singing the old minstrel tune “Let Me Sing and I’ll Be Happy.” The video plays behind a set of bars, and as it continues, Gatson’s physical exhaustion from the performance is palpable. He does not quite wear “white face” as a comment to the minstrel singer’s burnt corky black, but wears the gigantic white nose and over-exaggerated mouth of a clown. Here, rather than simply naming racism, Gatson inserts himself right into it. It is not just his physical presence in the video that gives Two Heads in a Box its power, but his ability to offer a response to the racism of minstrelsy that usurps its power.

The Brooklyn Museum has recently acquired Sanford Biggers’s installation Blossom (2007), consisting of baby grand player piano that has a bodhi tree growing out of its center, surrounded by a neat circular mound of dry earth, with an overturned piano bench resting towards the edge. The piano plays gospel-tinged tunes in a minor key, periodically filling the fifth floor Cantor gallery with mournful sound at strategic intervals. “Sweet Funk: An Introspective” gathers a collection of Biggers’s videos, installations, and sculptures that focus on the artist’s preoccupation with trees, cosmology, pianos and their relationship to notions of blackness. Like Gatson, Biggers has explored minstrelsy by using the image of a clown. Shuffle (The Carnival Within) (2009) is a two-channel HD video installation of the artist and a young boy putting on clown make-up as they ride a commuter train through town on their separate commutes. Each takes great care in putting on the white stage make-up of the clown, drawing in the exaggerated mouth, eyes, rosy red cheeks and nose. At points, Biggers, in a bright blue jacket, red pants, and white button-down shirt flashes on the smaller video screen performing Caribbean martial arts moves and struggling to free himself from the tree he has been bound to with red rope. Calenda (Big Ass Bang!) (2004) also references the Caribbean martial art of the same name. Its installation of movement patterns painted on the floors and walls, illuminated by a glittering disco ball in the corner, read like dance patterns and celestial charts. Blossom, Lotus (2007) resembles a Buddhist mandala, but upon further inspection, the diagrams for slave ship cargo holds are revealed. The headphones to listen to Bittersweet the Fruit (2002), a single-channel video embedded in a tree branch, hang from noose-knotted rope.

While Biggers and Gatson confront difficult subjects unflinchingly, Biggers seems to have found a way beyond the difficulty. Perhaps it is his interest in the cosmological that hints at a more utopian view and allows him to critique the present and the past while leaving room for a different version of the future. Gatson, on the other hand, seems stuck in documenting and identifying racism, leaving his lost in an endless and tiring feedback loop.