The exhibition Vaginal Davis & Louise Nevelson: Chimera consists of one room in which twenty similarly-sized, hand-printed works by Vaginal Davis appear along the four walls of the gallery, encircling one large sculptural work titled Chimera, in black wood by Louise Nevelson. By juxtaposing the works with the promotional photograph—which features the two artists dressed similarly in plaid men’s shirts and head scarves, in what appears to be Nevelson’s studio with the word Chimera floating above Nevelson’s head—invites the viewer to make her own connection between the two artists based on the image. In the photograph, the two artists seem, at first glance, to be acknowledging one another—their bodies are turned toward one another, their mouths slightly open in recognition. In the press release from the gallery one paragraph is dedicated to Nevelson, one to Davis and then a final, third, to provide context to Davis’ works. Instead of providing context about the individual artist’s practice, the text focuses on the connections between Davis and Nevelson. This selective omission allows for inference—for ways of reading Davis and her work through the lens of Nevelson’s life and work and vice versa.

Nevelson was born in the Ukraine and emigrated with her family to Maine when she was six. Her father opened a junkyard and worked as a lumberjack. Both her parents struggled with depression, and Louise is said to have gone mute for six months when her father traveled to the United States, leaving the family behind. Once her father became successful and the family was wealthy, Louise’s mother put her energy into transforming herself. According to Laurie Wilson, author of the biography, Louise Neveslon: Light and Shadow:

Preparing for her infrequent forays into downtown Rockland, Minna Berliawsky (Louise Nevelson’s mother) would take her time. “Before she’d get dressed it would take her five hours,” recalls Anita (Louise’s sister). Louise later commented. bemusedly: “When she dressed up it would take her a month.” (35)

This idea of transformation, of changing one’s appearance to affect how others perceive one’s self is critical to an understanding Nevelson's life and work. Wilson writes:

Louise’s taste for ingenious improvisation started early, and throughout childhood she tended to extemporize, wrapping fabric around herself in novel ways, pinning white embroidered aprons and linen yard goods in remarkable ways, or creating hats out of unexpected items. (36)

Later in her life, Nevelson would use her face and body as if material for artwork—sculpting and ornamenting herself. She understood how much appearance mattered in the world and, in particular, the importance of self-performance in the art world. By constructing her persona—that of a strong Diva, a character who wore scarves and oversized hats, smoked and declared her body in large oversized coats, a mix of men’s clothing and fur lined women’s coats, large turquoise rings and always the black smudge of make-up around the eyes, and the multiple layers of eye lashes—this look, this fabrication of a character, worked both as a means to convey context she could not otherwise articulate while also serving as a kind of protective shield. Again, Wilson writes:

The reviewer for France-Soir observed that Nevelson was tall, still beautiful, not hiding her age, wearing false eyelashes and an elaborate headpiece that emphasized the purity of her features. She liked the artist’s looks to those of Queen Tiye, the beautiful mother of Akhenaten in the eighteenth dynasty of ancient Egypt, and pointed out that Nevelson had greeted the eight hundred people who had come to the opening with “royal reserve.” Almost in passing she also noted that Nevelson had produced extraordinary assemblages that combined architecture and sculpture. (284)

As Nevelson once quipped, “Every time I put on clothes, I’m creating a picture.”

According to Vaginal Davis’s own self-created legend, she is the child of a German mother, with roots in aristocracy, and a Mexican father. She has also stated elsewhere that she is the child of an African-American mother and a Mexican-American father. She came into prominence in the late 1970s as a participant in the Los Angeles punk scene with the creation of her zine, Fertile La Toyah Jackson (1982–1991), and her performance in the band the Afro Sisters. While her work at this time explored issues of blackness, she also explored her Chicana background through the band ¡Cholita! In her early musical performances, Davis displayed various aspects of her identity—presenting and refusing to obscure or otherwise avoid the spaces where complexity or incongruity occur. For instance, for Clarence, Davis wears white face and performs as a white supremacist militaristic character. In no way is Davis disguised when she performs this character, and disguise is not the point. Subversion—dragging male, dragging white, dragging military—subverting culture (straight, white middle class, white as well as white, middle-class, queer) is the point. As José Esteban Muñoz writes in Misidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics:

Performance is used by these theatrical musical groups to, borrowing a phrase form George Lipsitz, “rehearse identities that have been rendered toxic within the dominant public space but are, through Davis’ fantastic and farcical performance, restructured (yet not cleaned) so that they present newly imagined notions of the self and the social. (97)

Here, then, is one affinity between Davis and Nevelson: the practice of making identity through performance without erasing the gaps that occur between the self and the constructed identity. In this way, both Nevelson and David allow these caesuras to prompt their viewers to reconsider codified stereotypes within specific identities. José Esteban Muñoz termed Davis’ type of drag “Terrorist Drag.” Muñoz quotes Félix Guattari in his discussion of the theatrical group, The Mirabelles, as illustration:

The Mirabelles are experimenting with a new type of militant theater, a theater separate from an explanatory language and long tirades of good intentions, for example, of gay liberation. They resort to drag, song, mime, dance, etc., not as different ways of illustrating a theme, to “change the ideas” of spectators, but in order to trouble them, to stir up uncertain desire-zones that they always more or less refuse to explore. The question is no longer to know whether one will play feminine against masculine or the reverse, but to make bodies, all bodies, break away from the representations and restraint on the “social body.” (100)

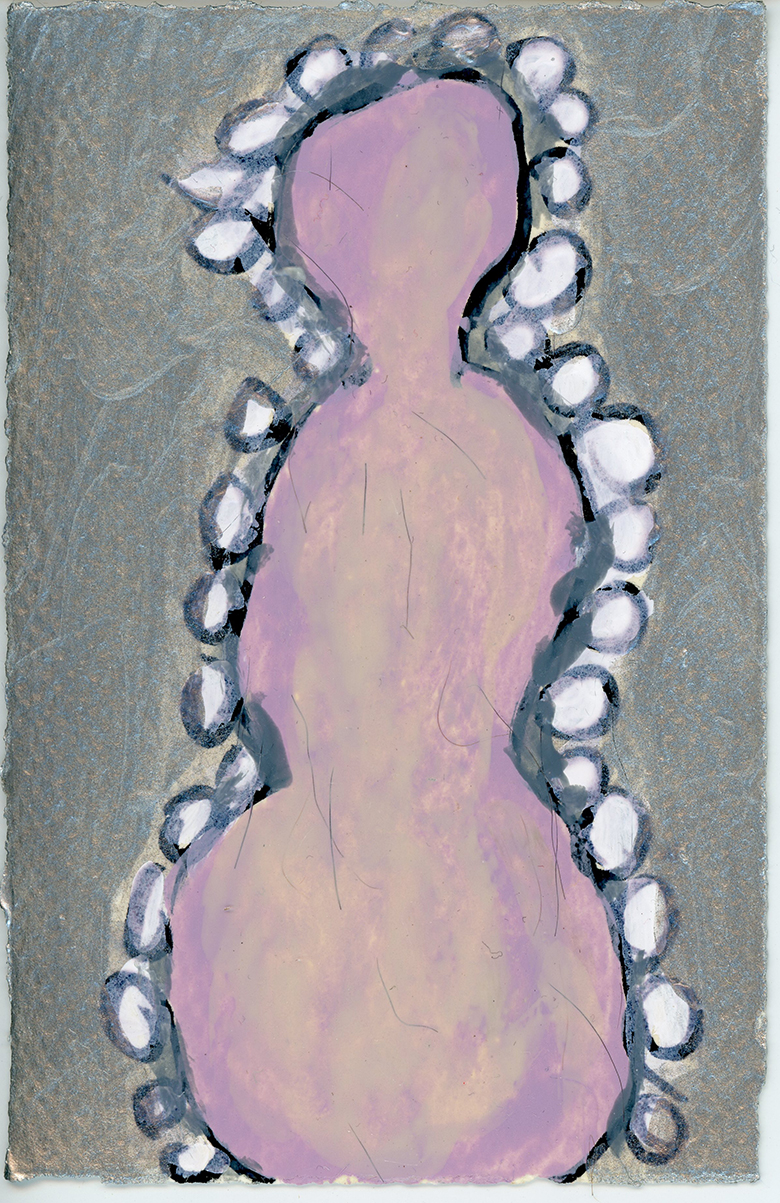

Davis’ twenty works are each hand-rendered paintings of an abstracted figure. Each has a different title, the name of a woman—most, women of color who are Hollywood and B-movie actresses, performers and singers. Each piece is painted in makeup: nail varnish, witch hazel, mascara, eyebrow pencil, pomade, perfumes, hair spray and conditioner, and others. In other words: in the same way a woman’s image is made by makeup, each portrait of a woman’s body is also made by make-up, and by hand. The construction, then, of these pieces speaks directly to the drag aspect of performing femaleness and its performance as a construction, as Judith Butler made clear in her seminal 1990 text, Gender Trouble. In essence, a person is a blank slate. As Butler writes, referencing the French feminist Monique Wittig, “…one is not born female, one becomes female, but even more radically, one can, if one chooses, become neither female nor male, woman nor man.” (144) Also much of this construction speaks both to Davis’ childhood memories of her mother’s making herself up with products as well as her own DIY philosophy.

Davis’ miniature paintings speak directly to this. Each is similar to one another: they are all small, abstracted, figures rendered to appear ephemeral and cloud-like. All the works share a milky-white appearance. The bodies are painted variations of: white, pink, peach; some of the bodies have streaks of black in them. The figures differ from one another in subtle ways. Some figures, for instance, are outlined in red or white circles. Some bodies are filled in with different hues, suggesting different auras. What makes a figure female, I wondered, as I walked along the room of images. Is it an aura? Some of the bodies seemed more masculine in my mind—taking up more space or appearing boxier—but how, I wondered, do these attributes make one more masculine or more feminine? In other words, because the figures are quite similar and yet do not clearly register as female or male, the questions looming are: What is female? What is gender? Because the images are created out of make up—the very magic that renders one “female,” to begin with—the question becomes more pressing.

The question of what makes one “masculine” is further troubled by the large work by Nevelson fixed in the center of the room. Situated in the center of the gallery space is a large, black, wood sculpture constructed of a series of geometrical spheres, which cannot be described as what one would term “feminine,” if by “feminine” we are to use the standard definition of the word: “Having qualities or appearance traditionally associated with women, especially delicacy and prettiness.” Creating work that disrupts this idea, and here we ought also take into consideration the time period in which Nevelson made her work—in the midst of the male dominated Abstract Expressionist movement —puts into question the very definition of the word “feminine.” But what, then, does feminine or female art work look like? What, then, does a female body look like? Furthermore, this large, tall wooden abstract sculpture constructed of a myriad of smaller black wood bits is not representational; but instead becomes something entirely different, something new. And yet, Nevelson’s sculpture, centered in the middle of the gallery space with Davis’ framed paintings of figures, encircling it, appears as if it could, indeed, be a figure.

The second important connection between Davis and Nevelson is the impossibility of passing. As a participant in the punk movement in Southern California, Davis, though a participant, could not become absorbed into that scene. Punk, though considering itself subversive, consisted (and still consists, though to a lesser degree) mostly of white, male bodies. And yet Davis was deeply informed by the punk/zine movement. As a queer artist, Davis can’t be fully absorbed into the predominantly white American queer movement. In addition, issues of socio-economics and of being mixed race further complicate Davis’s standing. Intersectional and indigestible, Davis uses these places of incongruity and complexity as starting points for dialogue. As Davis explains in Dazed Magazine:

My form of drag doesn’t placate mainstream sensibilities. I’ve always had this unease with the wealthy and privileged and do digs at them in my work. Now drag’s on television. RuPaul has a regular mainstream show, but she came out of the same underground scene I did. My cousin Karla Duplantier got me into punk. She was the black lesbian drummer of one of the earliest LA punk bands, The Controllers. It was the only scene that allowed me to get on to stages.

If you were a black drag queen you had to represent like a black diva and sing the songs of a black diva, but I was writing original songs and my persona was a sexualizing of political activist, Angela Davis. The original punk scene was very female-centered and art-driven. But by the advent of hardcore it had became all suburban testosterone and conventional. Punk lost its drive, and that’s when people like me and Bruce LaBruce and GB Jones in Toronto were doing our own little things that later became known as the queercore scene..

Drag performance strives to perform femininity and femininity is not exclusively the woman of biological women. Furthermore, the drag queen is misidentifying, sometimes critically and sometimes not, with not only the ideal of woman but the a priori relationship of woman and feminist that is a tenet of gender-normative thinking. The “woman” produced in drag is not a woman, but instead a public disidentification with woman. (108)

In the end, Davis provokes viewers to consider the place between cohering: the small paintings are not portraits of women, per se, but depictions, fabrications. Made up of make-up and constructed by hand, as women often are, the works reminds us that both a person’s identity and a person’s art are a fabrication, as is the case with Nevelson, whose appearance served as performance and a necessary addition to her artwork. As her biographer, Laurie Wilson, writes in Louise Nevelson: Light and Shadow:

When her beauty began to fade, what had come naturally when she was young required ingenuity and flair. As she got older she became convinced that in order to lift herself up above other talented female artists and become better known, thus making her work more salable, she needed a more arresting personal appearance. Being different, she decided, meant looking different. Thus began the development of “The Nevelson,” as her friend Edward Albee termed the persona she created and presented for public consumption. (348)

The personae that both Nevelson and Davis construct are necessary for providing context to the work—though context without text, allowing for a more nuanced and perhaps complicated means of adding a backstory.

Vaginal Davis & Louise Nevelson: Chimera

Invisible Exports

September 8 – October 22, 2017