In her recent exhibition at Leo Koenig, Lily van der Stokker created cartoonlike murals and drawings with fluorescent colors, bulbous shapes, and short, catchy texts. With images of flowers, clouds, and assorted handmade furniture (motifs she has mulled over since the early ‘90s), her work is meant to examine the notion of femininity. For van der Stokker, femaleness within contemporary art has been historically trapped behind the nice, the decorative and the pretty.

Van der Stokker’s process begins by making quick compositions on paper in small sizes with marker, color pencil, and ink. These drawings look like the dreamy doodles made by a young girl paired with the efforts of a rather garish interior decorator. Tasteless, floral, Technicolor wallpaper patterns float behind gaudy sofas and puffy armchairs. Texts, often suspended in thought bubbles, will declare statements like “Terrible Artwork” and “I am ugly.” Once finished, van der Stokker replicates these images on the gallery wall, allowing them to expand and play with space. The decorative candy-colored swirls rise high across the wall, often reaching onto the ceiling, while child-size furniture, seemingly made by the artist, brings the illusion into three dimensions.

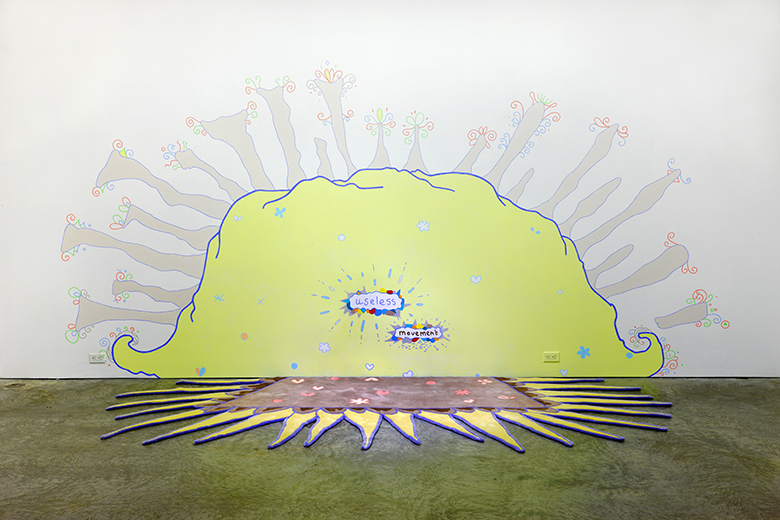

In theory, van der Stokker’s work succeeds best when her drawings become full-scale installations. In reality however, her enormous blobby forms create an interior landscape that is not much more than an overly designed living room, vacuous and depressing. The murals are decked out in patterns of plaid, with geometric shapes, and other whimsical squiggles, while actual sofas (upholstered in matching fabric) are pushed against, and sometimes fastened to the walls. One piece, Useless Movement (2010), even extends its design onto the ground, stretching across the floor in the form of a fluffy, lime green rug. In an attempt to place preconceived notions of the decorative and female space on display, van der Stokker may have made the case against it.

The difficulty with this exhibition is that it appears to rely on a concept that is hard to buy into. Works of art that are at once beautiful and conceptual (Georgia O’Keeffe’s flowers or Judy Chicago’s installations) subtly stress perceptions of femaleness, and with more intellectual substance. Van der Stokker has, instead, chosen to trumpet ostentatious “feminine” art that revels in its inherent kitsch, offering no more than a cold feeling of detachment for the viewer. Van der Stokker’s pale references to pro-feminist ideals and anti-art establishment credos feel forced, as opposed to offering any real insight into her experiences as a woman artist.