Films, sculptures and artfully wielded hole punchers juxtaposed with familiar and abstract subject matter make up British artist Lucy Skaer’s first solo project in New York: Rachel, Peter, Caitlin, John. The exhibition is a sort of visual puzzle, which if you spend some time connecting the pieces will illustrate notions of interruption, reinvention and the alchemy involved in filling in the missing parts of vision.

The cinematic component of the show is made up of three 16mm films that run on loops from separate projectors pointed at three different walls. The films run simultaneously, enveloping the viewer in a three-sided onslaught of images. Placed on a one-foot high table within the space are nine sculptures, each made from a single material: bronze, copper, pewter, black wood or porcelain. The sculptures are similar in length and girth to baguettes, but shaped differently from one another, most noticeably at their ends. For example, the tip of one forms a plus sign, another a square.

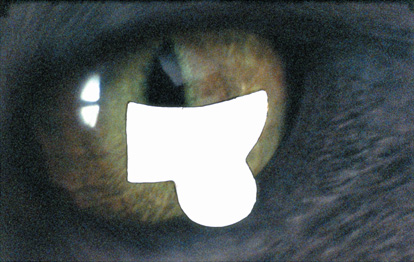

Skaer’s live-action color films showcase one subject each that include close ups of a cat, a Rothko painting and images of pages from a Gutenberg bible. Initially, this combination of subjects raises the question as to whether Skaer is attempting to depict, in some way, similar or dissimilar aspects of nature, the artworld and religion. Is it her aim to illustrate discontinuity or to suggest similarity among her subjects and her mediums (sculpture and film)?

Things start falling into place as each of the projected images begins to intermittently include oddly shaped white sections whose function is to remove a chunk of the images, rendering them incomplete yet recognizable. The film of the cat, for instance, is still perceived as a cat even when sections are absent (like missing puzzle pieces). Attentive viewers will notice that the ends of the sculptures feature the same shapes as the spaces removed from the frames of the films. Skaer seems to be making a statement about how perception and representation are organized. The projections emphasize the two-dimensionality of images of three-dimensional objects, while the sculptures on the table embody the viewer’s tendency to infer more than she perceives, to constantly augment her basic perceptions by “filling in the rest.” In Rachel, Peter, Caitlin, John, Skaer draws us into a stimulating encounter by requiring a self-reflexive assessment of our senses; she deconstructs our perceptions by interrupting our habitual, naive gaze.

Fall 2010,Degree Critical

Monday 11/29/2010

Rachel, Peter, Caitlin, John

byJillann Hertel (2011)

The Year That Was: Degree Critical Reflects on 2020

Contributing writers consider the most meaningful works of art, from any time and genre, for getting through 2020 Continue reading...

The Sight of Death, Over and Over

Alumna Cigdem Asatekin (2017) considers how two paintings in puzzle form helped to pass the time under the Covid-19 lockdown Continue reading...

Fallback Friday: “Doris Salcedo: A Mourning Offering”

Degree Critical revisits alumnus José Peña Loyola’s (Class of 2016) walk through this 2015 exhibit with his mother Continue reading...

Listening With the Ancestors: Cauleen Smith’s “Mutualities”

Student David C. Shuford (Class of 2021) reviews Smith’s first solo exhibition in New York Continue reading...

Fallback Friday: BYOF-Bring Your Own Flowers

Alumna Christine Licata (Class of 2008) reviewed Ei Arakawa’s 2007 intrepretative performance of Amy Sillman’s artistic process Continue reading...

Fallback Friday: Wet Suits and Male Gaze

Degree Critical revisits alumna Tara Stickley’s (Class of 2013) timely reflection on the eve of Trump’s inauguration in 2017 Continue reading...

Renée Green Holds Chromatic Space for Critical Contemplation

Kirsten Cave reviews Green’s current exhibition “Excerpts” at Bortolami Gallery Continue reading...

The Face of a Contracting World

Student Nyasha Chiundiza (Class of 2021) considers how the Covid-19 pandemic exists within Bruno’s cosmos and its rhythm of contraction Continue reading...

Fallback Friday: “Dispatch 33: It’s the Communications Environment, Stupid”

A 2016 dispatch written by Chair David Levi Strauss forecasts American democracy’s “digital doppelgänger” that now grips the nation Continue reading...