Apart from historical accounts written by the victors or the victims, flies-on-the-wall or gadflies, fables and folktales are excellent gateways to understanding culture. Perspective is grounded, respectful yet intimate, with a humility that defers to humor, which in turn resonates with hope and compassion. Conversely, fables and folktales can also be frightening and fantastical, alien from everyday life. This enhances the particularity, power, and appeal of stories that present the complexity of human life. Perhaps the previous statements qualify as an elegant cop-out, a way to skip the bulky, stately tomes for a volume of slim and potent bedtime stories.

Sound artist and composer Raven Chacon’s Still Life No. 3 (2015), currently on view in “Transformer: Native Art in Light and Sound” at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York, interprets Diné Bahane’, the Navajo creation story, though a multimedia and multi-sensory work. Diné Bahane’ relates the emergence of the nilch’i dine’é, or air-spirit people, from their underground domain to the surface of the world. They gradually transform into nikookáá’ dine’é, or earth surface people ready to form clans and societies. The exhibition space shifts according to four colors sacred to Navajo people and their corresponding temporal states: white for dawn, blue and purple for midday, yellow for dusk, and black and red for night. A recording of the creation story is chanted, reverberating from a line of suspended speakers in the middle of the room. Different parts of the story are conveyed by blurring linearity and revealing the narrative as a cycle.

Excerpts of the story in alternating Diné and English hang from the wall on transparent text panels. The gallery lighting casts shadows of the text upon the walls that serve as visual echoes.

From top to bottom through Tsoodzil in the south they ran a great stone knife to fasten it to the sky. Then they adorned it with turquoise. They adorned with dark mist. They adorned it with many different animals. They adorned it with the heavy mist that brings the slow, gentle female rain.

This passage, one of the texts on transparent panels mounted on the wall surrounding Chacon’s sound installation, considers the repetition and unfolding of the story’s narrative. First, the air-spirit people, in their slow yet persistent transformation into earth-surface people, tether their world to the sky with a great stone knife—a gesture that is primal and urgent, done in order to establish bearings. Then comes the adorning that resembles nesting, building a home in the shape, smell, and sensations related to comfort—a home or a soft world founded upon the hard kernel of enterprise and work. And finally, the “slow, gentle female rain” comes from the heavy mist. There is, now and always, a world that is constantly moving, transforming, dreaming, and creating.

Imagine a woman emerging from a cave. Purple light illuminates her face. A chant echoes behind her, diligence and affection nestled within each uttered syllable. In the voice is a kind of ruefulness that paves way to determined hope. There is an acknowledgment of the difficulty of life, yet this does not stop the voices from pursuing and finding a kernel of joy. Sounds overlap and words weave into each other, dissolving into warble, until the entire narrative takes on the shape and movement of water and wind. The woman makes her journey into another cave to repeat the same story, to conceive more worlds by dreaming and chanting. Will it have a different outcome? Will one world be different from the one that came before.

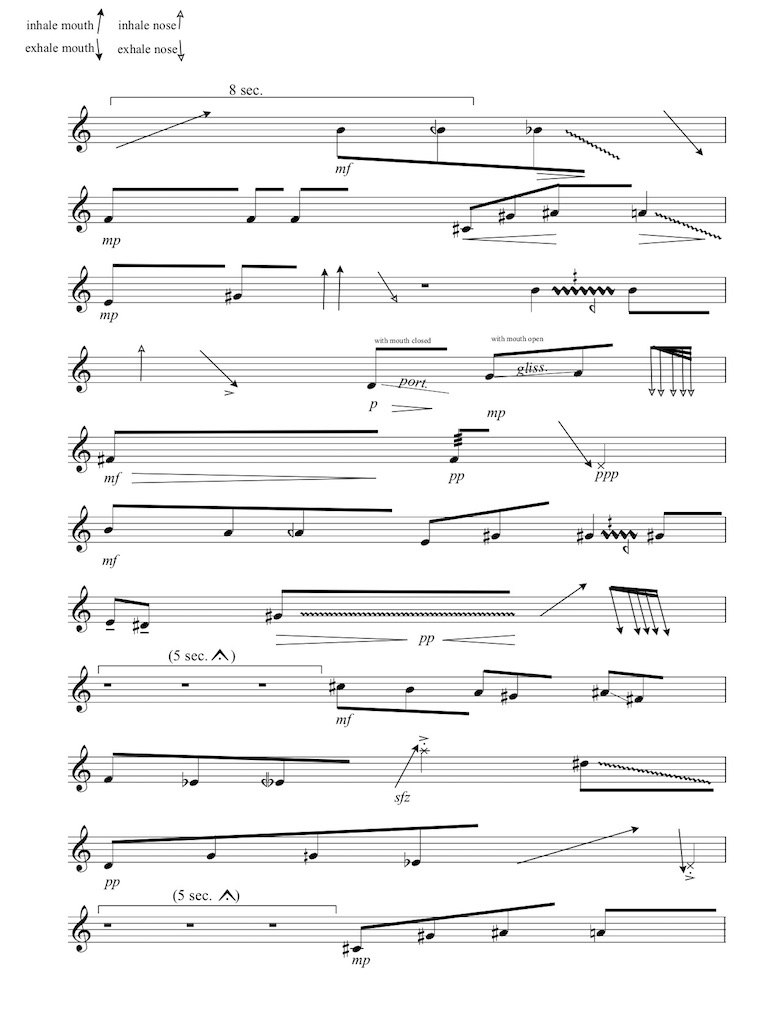

One of the ten Native artists featured in “Transformer: Native Art in Light and Sound,” Chacon (b. 1977, Fort Defiance, Navajo Nation) is known for his chamber music, which pushes the boundaries of European musical instruments to produce music with distinct qualities. In The Journey of the Horizontal People (2016), for example, violin and cello bows are scratched against strings, and double notes are drawn to produce music that resembles natural sounds or noises: seagulls over the beach; the thin, lingering voice of the wind over canyons and mountains; the huffing of a wild animal. Another notable work in his corpus is Ella Llora (2002), where the heartrending cries of an Albuquerque woman in a court deposition were translated and transcribed into classical European notation. Originally recorded into a found cassette, which has since been destroyed, an excerpt of the work can be found on the artist’s website.

As with Still Life No. 3, Chacon’s sound art contains a humanizing horror, a flash of illuminating terror beneath a surface of composure and wonder. A sense of play also complements the complexity and depth of Chacon’s sound art and installations, like the way simple and cartoon-like lines of ancient cave paintings harbor powerful suggestions. It is consciousness as we know it or, perhaps, as it knows itself. Trembling and growing inside a cave, before a glowing fire and, perhaps, a puddle of water that served as the first mirror for the mind. Terrifying and tantalizing at the same time, to know that one is here and one exists.

Stepping into the installation of Still Life No. 3, one might not be able to tell, just by listening, where the story begins or ends. It seems that it always is and will be. Its timelessness contains an assurance of continuity. One might not know all there is to know, but one will always be able to proceed with caution into an unknown moment in time unfolding before one’s eyes. Everything is ever present. Viewers are granted emergence into the world and perspective of the Navajo, who have developed through centuries a deep relationship with the natural world and the spiritual.

Our interpretations of myths, how they have been used to forward ideologies and perspectives, reinforcing hierarchies, the idea of overcoming rather than undergoing the foreign or unknown, can be reconsidered. Hand in hand with tradition, they can invoke ideas of nationalism and supremacy, fealty to a singular group, and a disdain for progress. Myths can lead the social body to a plateau, where it must imagine or hallucinate movement and progress when it is rather condemning the life of the social body to complete stasis. This reconsideration also encourages us to question our own ways of seeing and understanding the knowledge that is transmitted to us and what we do with it.

A creation story, on the contrary, has the ability to flawlessly transform through time. Hence, the title of the exhibition “Transformer” is portrayed by Still Life No. 3, even though it’s technically a myth. What then, makes the artwork and its source, the Diné Bahane’, potent and timely in its untimeliness, in its divine earthiness?

The Diné Bahane’ rather speaks of the emergence of a community from the shadows into clarity and color, into the entire spectrum of existence. There is an intimate homage to life in its glory and agony. Chacon, naming his artwork a “still life,” amplifies the work’s exploration of a counterpoint in movement and transformation. Still Life No. 3 makes a case for dreaming, conceiving worlds through fables and folktales without grandiosity through its form, a sound and light installation, and content, as an emergence story rather than an origin story.

“Transformer: Native Art in Light and Sound” remains on view at the National Museum of the American Indian, 1 Bowling Green, New York, through January 6, 2019.